by

Amanda R. Howland

Originally published in Moonshine Baby online literary journal, March 2015

Sleep—in a sleep like charcoal unsettled on black construction paper. Sitting asleep—mouth sealed.

A sleep so heavy, it was work. My body knew we were in a car, wrapping around mountains. Black trees rising up on my side, dropping off on his side.

A long black moment—then brakes before impact—desperate breaking jolt. He said shit and I didn’t want to open my eyes but I did.

It was so dark—night in that old country with no lights—Virginia mountains.

Neal—the man who was my husband then—looked at me, smiling because we were alive. There was only the sound of our breathing.

A deer, he said. And there was blood on the glass in front of our faces.

We were coming back from a vacation in Nags Head, North Carolina. We’d split from my brother and his wife—they drove back through Maryland. I wished they were still with us.

Still waking up, I stood with him off the side of the highway. We weren’t safe in the dark sedan, we figured. Afraid to leave the lights on, who knows how long we’d be here, and we didn’t want to drain the battery. Traffic was sparse but treacherous. The cars flew past us, invisible, shaking the Toyota. With the hazards on, we waited in the dark curve of the road. So we got out—our cell phones weren’t picking up reception in these black mountains. There wasn’t much of a shoulder. Cicadas, frogs, crickets made sounds around us. The grass was wet against my ankles.

He lit a cigarette. I went for his free hand, he squeezed my hand fast and let it go.

I wanted to help—to figure something. I opened my useless cell phone again. Searching…it said. I shone the weak light of it around, to see, and there a few yards behind us, was the white bottom of the deer, the deer on its side, still. I closed the phone. The vision struck me with a physical pain rising from my guts to my chest.

Neal opened his phone and looked back at the deer a long minute. “Well, I guess you were right, Mu, we should have left earlier.”

Not long, maybe twenty minutes, or forty, a car slid in behind the Toyota. The walking light of the state trooper moved toward us.

“Hey, y’all better get from that ditch. There’s rattlers down in them grasses.” Her voice was stern and raspy. It was too dark to see her face, just the unmistakable outline of the forward-tilted hat.

I gripped Neal’s arm, afraid to move. He jerked us forward, back onto the tar road.

“I didn’t know…” I said, “We were hiking in Sedona a month ago, we heard a rattle then, but, I didn’t know they weren’t just in the desert.” How could it be – in this humid green night.

“Oh yeah, ma’am, they mate down there, liable to be a dozen or more there now.” Her flashlight glazed off the mirror and lit up her face, revealing tiny features recovering from a smile.

We were grateful. It was sometime close to midnight. The trooper drove us into a town, told us this town, believe it or not, had just installed indoor plumbing three years ago. She’d take us to the man who could tow our car to his garage, and then give us a ride to a hotel by the highway.

In the back of the police car, we sat still behind the solid partition. I wondered about the plumbing and the darkness. How could it be—in America? I looked over at Neal. He turned and gave me a fast smile, a reassuring wink. We’d been married seven years. He was skinny, white and poreless with thin red hair he parted unnaturally on the left. His eyes, once disturbingly beautiful to me, heavy lidded and dark red brown, now seemed to bug out a bit.

Our week at the beach! I’d laughed so easily with my brother. Sisters and brothers have the same humor. I felt lonely for it now. Neal and I couldn’t laugh together. Did Neal even see the faint flicker of superiority on the elfin officer’s lined face when she said this town had just received indoor plumbing? Smug pride that hertown was more cosmopolitan than this one?

Neal would say I was being mean, but I thought it funny in a friendly way—we are all susceptible to foolish comparisons of our town to the next.

It seemed all night till we were in the hotel an hour away from the village in the mountain where the tow man and his wife lived. I felt sleepy like a child, pressed between Neal and the window of the tow truck. The guy was nice enough to drop us at the hotel after he dropped our car at the only garage around.

We were broke, had no credit. Ashamed, I called my brother and asked for help—they were almost home, back in Ohio, but he gave me his wife’s credit card number, said we could charge it all and then pay them back over the rest of the summer. My stomach knotted up.

The hotel was incredibly new, as if forest had just been cut to make way for this commercial strip along the highway, corporate billboards guiding the way. But I had no reception.

In the room, Neale automatically flipped on the TV. The TV showed women with black hair and dark tans getting pedicures, then a reality show about prison, then a game show about war, then a reality show about meth, then a reality show about bridezillas, then a commercial for a hamburger with many patties, then a commercial for floor wax. Bees flew out of the rays shining from the floor.

And I felt suddenly awake.

“Hey Baby, let’s have a hotel party!” I jumped off the bed and onto the floor in front of him.

“Let’s not, Mumu,” he lay on his belly channel surfing. The sound of the TV made me sick – we never watched network or cable at home, just streamed shows. Commercial TV disturbed me. The racing images, the banners and emblems stuck on the screen – I couldn’t believe people put up with it.

Neal wanted me close, but not to talk to, not to touch. Just to be near while he watched compulsive instant Netflix viewings of Nip Tuck, Prison Break, and any law show. If I picked up a book, or my phone to text, he’s look at me sideways and say, “Now Muriel. Do that on your own time.” Meaning, when I am home and he is not. Which, being that he was rarely employed, was not often.

After being trained these past seven years, I would sigh like an adolescent and obey. If I picked up the book or phone again, he would yell my name, hit my hand.

Once I wrote on the back of an envelope a deal: I would not text while he was in the room, and he would drink with me and listen to music with me once a month, maybe on a Thursday night.

He laughed, he said, you’re so silly, Mu.

I said, no, I’m not happy, I need to have fun. I need to have someone to talk with, you to talk with.

He said, you arehappy, you don’t even know about unhappy. Go make me some coffee. Then he pinched the soft part of the back of my arm, hard. I winced. I said, I hate that. He said, oh you love it. Go on now. Chop chop.

“Well, maybe I’ll go see if there’s a bar downstairs, or a convenience store, get some wine or something.”

“Just stay put, will you? God Mu, such a drink drink drinker – didn’t you drink enough with your brother this week? And don’t be stupid, you know there’s no bar in this place.”

“I’ll just go for a walk then—it’s a gorgeous night.”

His face glowed blue as I put my boots back on. He held the remote tight, but wouldn’t press mute, he looked over and said, “What the fuck, Muriel, get back here, come on, it’s ridiculous to go walking around, shit, it’s almost three…”

A sudden Jolt—a blind jolt like someone ramming their elbow into me, and I staggered, but nothing was there.

“Yeah, I’ll be back.”

“What’s wrong with you—why’d you fall like that?”

“I’ll get you a candy bar, if I see a machine,” my throat felt tight, “I love you, Neal.”

He turned back to the TV, “Yeah, whatever, love you, too. Don’t forget your key.”

I rubbed my shoulder—I swallowed my desire to cry when I passed a couple of women, mother and daughter maybe, silently going to their room. What hit me in there? It was like the air had become a wall and rammed into me. Could there be a ghost in such a new place? Or from what was here before this place?

I just wandered the halls, the light dead and awful, useless. Everything smelled new, what was that smell? Drywall and glue.

I was outside myself. Arrested, examined. Moving down the halls, I could see still images of myself from three angles: face slack, the light imprinting me in this dimension faded, first red, then cherry pink. I felt the weight of the corpse I had become, alone in this marriage. Eyes dull. Guilty.

There were just two floors. Soon I was wandering around on the first floor. The only soul around was the front desk woman, who asked me if I needed any help finding anything. She had a black and red wig that looked squished on one side like she was napping on it before I came around. It didn’t look very soft. I said, no, I said I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t bother asking about a gas station, too late for anything.

She adjusted her wig and turned toward a muted television. She looked how I felt: heavy joyless eyeliner, exposed skin, skin dented from unfriendly surfaces.

My throat was swollen with sorrow—I wondered if carrying this sorrow all the time would affect my lymph nodes. There was no chlorine smell in the hotel, no coffee smell. I stepped out front—the night heat felt good—I’d forgotten it was spongy summertime—my fingertips numb from the air conditioning. So much power to keep this place cold, and how many of us were here tonight: a dozen people at most? The highway rushed from the darkness, and the crickets.

Then—a slap hard on my back and I stumbled forward, falling to my hands on the hard concrete. My wind was knocked out of me—no one was there. Embarrassed, I looked through the glass windows, but the front desk woman was faced away from me, toward a screen.

I sat back on the ground, catching my breath, looking at the palms of my hands, scratched and bleeding a little, as well as my right knee.

I was having a stroke, or a seizure of some kind. A brain tumor was pushing on the part of my brain that keeps my shit straight.

I felt strange calm in the panic, wondering, what next, and, will I die here, and I sat for a long time.

Back in the room, my eyes dry from too much wakefulness. He was sleeping, soundlessly as always. His hand lay still stretched out across the cover, so peaceful. I ached. I wanted to reach for his hand, to touch him and be touched by him. Flickers of our first days together, sitting in the café at the art museum with acorns falling around us, hugging at the beach, sitting around a fire with Halloween paint on our faces, these flickers rose up then fell away. They were losing their power. I’d held them close for seven years, but three sweet months followed by six years and nine months of—something like tension—and their power was fading.

I remembered the candy bar, so I slipped out again, but only had 72 cents, there was nothing.

The room was dark, except for the blinking red lights on the DVD player. I turned away from him in bed, because he didn’t like our skin touching while we slept. I thought my eyes would not seal shut, but just stay open over the dry air, but no, I fell asleep fast.

In my dream, I was standing on a rock, at the edge of a mountain, over a valley. I knew there was a fire somewhere down in between the mountains, but I couldn’t tell if it was day or night. The forest moved behind me—I sensed Another at my back. I knew then who was there. The Bear grasped my shoulders in his paws, hard, but I stood still. I could smell his musk, and the paws were larger than I would have thought. He began to shake me, and occasionally a claw grazed my cheek, but I didn’t look back, or fall. He shook me harder, and I began to cry, but it was honey-crying—sweet streams of honey pouring down my face, pouring into my mouth, down the front of my body, down to the ground and down to the valley below.

(I knew him like a Mother. I felt safe in his ravaging.)

Then, with a grunt, he tore off my arms, and I didn’t fall. Suspended. And the honey cleared from my eyes. And then he tore off my legs and I hovered over the town. My torso rang through and through like a clanged tuning fork. He tore my head from my trunk and threw my body parts down to the fire, and I flew away.

Of course, morning came fast and hard. Nothing was easy, and the continental breakfast was over at eight, before we got up, and the shower had a weak stream, and the cell phone etc. etc.

And of course, the car was so damaged, we’d have to rent one, and somehow, get this car ten hours home in a few weeks. And my brother had to give me a second card, and I was ashamed, and felt guilty for the thousandth time, that I didn’t make more money. And angry at Neal etc. etc. Old bruisy feelings, our vacation most completely over.

We had to take a cab to the rental car place. (We were so hungry.)

We waited in the heat an hour for the cab, first in the cold hotel lobby, then in the heat out front. Then, a banged up flat grey Chevy from the eighties puttered up and stopped in front of us. The cabby, also flat grey, ushered us in like a grouch, as if, of course we were supposed to recognize this unmarked jalopy as a commercial service vehicle.

Of course we were, because, as George the cabby told us, he was the only cabby in town. He was known. George wore a black Greek fisherman’s cap with a peeling sticker on the side facing me. I wanted to read the sticker’s faded blue lettering, but I didn’t want to stare, so I only caught “-asps!”

I sat up front and Neal sat in back. We did not stop at the first stop sign down at the bottom of a hill. We slid on into the intersection right in front of a speeding truck that slammed to a stop and honked for a long honk.

“What’s his problem,” said George.

I looked back at Neal and we exchanged a yikes look.

We rode slowly down a lone state route that gradually turned into a main street lined with two-story buildings from a hundred or more years ago – businesses with apartments above.

“Hey you old coo!” George stuck his hand out the window at a man sitting outside a barbershop smoking and reading a paper. He stopped in the middle of the road, but it was okay because there weren’t any other cars.

“When you opening up, George?”

“Gotta run these ‘uns to Gladsdale, then I’ll be back, better side an hour.”

“I’ll be here.”

Slowly the cab pulled forward again. George said to us, “See, I’m the town’s only barber, too.”

I looked back at Neal again and we smiled. I was feeling good for the first time since back at the beach with my brother and his wife, with the ocean in front of us, a warm kitchen and deep drinks.

I could never figure out whyour days at home were so difficult—it didn’t seem like they had to be that way.

But I reached back and Neal squeezed my hand. I felt calm, and suddenly looking forward to being back home. After this bumpy cab ride, once we settle the paperwork and got into some boat of a rental, I would look out the window and daydream about the changes I’d make when we got back home. The new routines, rituals, rhythms, the way to finding happiness again with myself, and with Neal.

We were approaching what seemed to be the main intersection of town, and George put on his turn signal. It ticked loud and fast. As we got closer to the red light, I saw a dog across the street, a big moppy dog running between people on the sidewalk. I laughed—the dog was clowning and the people were enjoying him. His red tongue flapping against his big white body, running from this person to that, stopping to roll, hop back up and side to side.

Then the dog walked into the street and I worried for him—but there were no cars, we were coming to a stop, and the dog was walking slowly.

I turned to Neal to point out the dog, but then George wasn’t stopping, and I turned back to see the dog walking diagonally across the intersection, and everything was moving so slowly, but instead of saying stop, I looked back at Neal, and then I heard the yelp, the cry of the beast, and felt the bump as we ran him over.

My stomach rolled. I looked back to see if he was lying in the street, but we’d turned. Moving fast away from the town, down long country roads. Riding up, and then down. I looked at George—his eyes were inscrutable, aged like wood, maybe he only knew the road by feel. His feet charged the gas and brakes with no regard.

After a long minute Neal gave a nervous little laugh. “Jeez, Mu, how many animals are we going to hit this trip?”

George snorted. “There’s critters jumpin’ out at you from all sides these parts.”

I couldn’t look back at Neal. The guilt waved through my body. My heart was with the body of the white dog.

When we got to the barren industrial park that housed the car rental office, I got out fast, feeling like I was going to vomit. I was grateful to Neal for dealing with George.

“What’s wrong with you?” He squinted in the sun, his hand shielding his eyes.

I was bent over, breathing hard with my hands on my knees. “That dog—Jesus, Neal.”

“Oh, that,” he laughed, “That dog’ll be fine, Mu.”

“I don’t think so.” I stood up and looked at him, my face laced in cold sweat.

This thing between us—it was contempt. Contempt I saw in his face, for the words I said, and for the movements of my body.

“Well. Come on, chopit, Muriel, I want to get out of this sun.” He clapped his hands and walked ahead of me into the one-room building.

We stood in the rental office. The carpet was blue like a boy’s new room, and the walls were blue, and the whole thing smelled like the hotel, new wood and glues and paints. There was no music, just the receptionist, holding her index finger up to us, saying, just a minute.

We didn’t look at each other. We stood apart with our hands not touching. The new air, cooling and sweet like canned water, the new air seemed to expose the field between us. We were waiting for a safe car, however expensive, to take us back to Ohio. We didn’t look at each other.

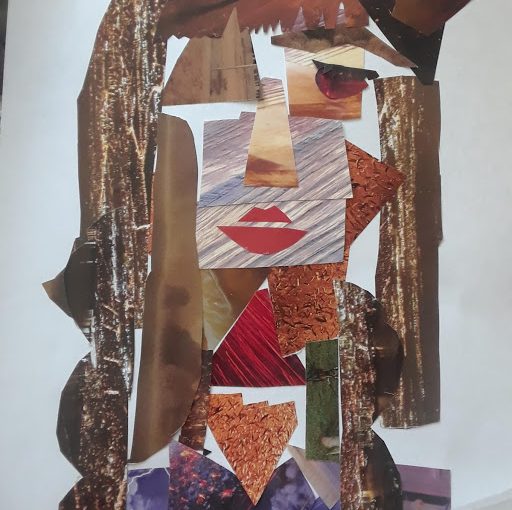

I looked instead into a painting behind the receptionist. It was loud and out of place here, framed in garish yellow wood, slightly crooked. It was a messy sunset—paints of melted egg yolk pouring into heavy golden water. Rough black trees scattered on the shore, some reaching veiny into the sun, and then repeated on the water. A forest somewhere, a dark molten sun.

THE END